I recently had the pleasure of hanging out with a bunch of very clever pain people at the Paincloud Convention in Norway. Among the group were two researcher/clinicians that I have long followed in the pain research world – Dr Tory Madden, who gained her PhD within the Body in Mind team in Adelaide, Australia, and Dr Kjartan Vibe Fersum, who worked with Professor Peter O’ Sullivan and his Pain Ed team. Both were delightful to meet in real life and each presented their research at the convention. I am going to give an overview of both presentations over two blog posts.

Having quoted his research so very many times throughout my masters degree, read everything that has been published on the subject and attended a two day workshop presented by Peter O’Sullivan, I was excited to meet Kjartan Vibe Fersum and had to stop myself from displaying any fan girl behaviour! Kjartan and his wife Anine, both Physios were a delight to hang out with – grounded and down to earth.

A quick ‘fan girl’ selfie of KJartan and myself

As it is with meeting many of these well known researcher/clinicians, you often walk away thinking that they are such personable people – and you can’t help wondering if the positive results that they demonstrate in their clinical trials have a lot to do with their ability to quickly create a rapport with anyone they are chatting with. If you have ever had a chance to chat with David Butler or Lorimer Moseley you might have had this experience also. This is probably not an accident – the science is slowly starting to paint us a picture that this stuff matters – creating a strong relationship with patients in the clinic seems to be more important than pretty much anything else that you do within that therapy time – many studies have demonstrated that the stronger that alliance with the patient, the better the outcomes they will get from that therapy (1-3).

Back in the mid 2000’s, researchers like Peter O’Sullivan and Wim Dankaerts were starting to move away from the popular theories of the time that revolved around instability and lack of motor control being the cause of low back pain. The biopsychosocial model of pain was being investigated and acknowledged more and more, and the multidimensional nature of the contributors to back pain were being talked about by researchers and clinicians. The Cochrane Back Review Group at the time recommended that on the basis of this, classification of low back pain into subgroups was likely to be helpful in directing both research and treatment.

O’Sullivan had produced what he believed was such a system – one that took into account the need to understand the patient and their beliefs about their pain well enough to be able to decide if faulty or unhelpful beliefs or social factors might be playing a role in the maintenance of back pain. As well as this, he felt it was important to look at what movements or postures were able to reproduce their pain, and how often throughout the day they tended to adopt those postures or movements. He published his proposal with some case studies to demonstrate the different approaches used for different patient presentations (4). Shortly after that, Wim Dankaerts published a paper showing that when 13 clinicians had been trained to identify the movement patterns described in the classification system, they were able to come to almost perfect agreement when presented with test cases to identify (5).

At this point, Kjartan took up the reins and designed a randomized controlled trial to test the theory and check that the results that were being produced, weren’t just due to those strong alliances created by this very charismatic, curly haired, Kiwi/Aussie

The process took five years and was done in Norway at the University of Bergen. During this time, Kjartan and his wife had two daughters. The results of the trial were a success (6). Even the most skeptical among us tends to sit up and take notice when we see results like this in a recalcitrant condition like chronic low back pain.

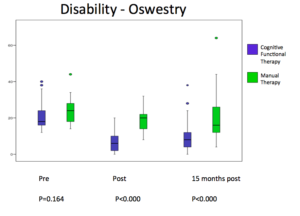

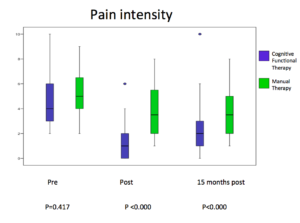

As you can see – the nearly 50 subjects in the Classification Based Cognitive Functional Therapy group (CB-CFT) did a lot better than the 43 subjects in the Manual Therapy and Exercise group (MT-EX) in disability and pain. This was also the case for all the other parameters that they measured. Importantly, there were big differences in patient satisfaction between the groups, the CB-CFT group being much more satisfied. They also displayed dramatically lower care seeking (utilisation of health care) after the intervention – the implications of which were not lost on me – in a system where you are going out of your way to ensure that you reduce distress, reduce fear of movement and increase self efficacy, it follows that the patient will be both very happy with the process and outcomes, and less likely to need further help in the future.

If you are interested to learn more about Cognitive Functional Therapy, you can check out some of these youtube videos, the Pain-ed website or get along to any of the courses run by the Pain-ed team. I can highly recommend it. The link to the article above is here.

If you are sad that you missed the Paincloud Convention (you should be!), check out their website to see the program. Then purchase the video package of the presentations when it becomes available – you won’t regret it – it was a wonderful, well rounded weekend of clinically applicable, entertaining and engaging presentations. See some photos below.

1. Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML. The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: A systematic review. Phys Ther 2010, Aug;90(8):1099-110.

2. Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, Latimer J, Adams RD. The therapeutic alliance between clinicians and patients predicts outcome in chronic low back pain. Phys Ther 2013, Apr;93(4):470-8.

3. Fuentes J, Armijo-Olivo S, Funabashi M, Miciak M, Dick B, Warren S, et al. Enhanced therapeutic alliance modulates pain intensity and muscle pain sensitivity in patients with chronic low back pain: An experimental controlled study. Phys Ther 2014, Apr;94(4):477-89.

4. O’Sullivan P. Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: Maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Man Ther 2005, Nov;10(4):242-55.

5. Dankaerts W, O’Sullivan PB, Straker LM, Burnett AF, Skouen JS. The inter-examiner reliability of a classification method for non-specific chronic low back pain patients with motor control impairment. Man Ther 2006, Feb;11(1):28-39.

6. Vibe Fersum K, O’Sullivan P, Skouen JS, Smith A, Kvåle A. Efficacy of classification-based cognitive functional therapy in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain 2013, Jul;17(6):916-28.

Some of the presenters chill out in the Norwegian mountains at a retreat before the Paincloud Convention. L to R: Sivgar Garfors, Matt Dennis, Tory Madden, Sandy HIlton, Ole Morton Salte, Alison Sim, Bronnie Lennox Thompson

The conference organisers Sigvar and Ole on top of the world.

L to R: Ole Morton Salte, Sigurd Mikkelsen, Kjartan Vibe Fersum, Alison Sim, Sandy Hilton, Tory Madden, Bronnie Lennox Thompson, Jason Silvernail, Sigvar Garfors, Tim Marcus Valentin Hustad.

Kjartan Vibe Fersum tells us that posture doesn’t have much to do with pain and that telling people otherwise probably does more harm than good

Jason Silvernail spoke about how it might be helpful if we as therapists placed less emphasis on the physiology side of pain science and more on the human side – understanding who our patient is and creating a connection with them.

Sandy Hilton speaking about graded exposure and graded imagery in pelvic pain populations – plenty of penis and vagina talk with a good laugh thrown in – but some great information about serious topics.